Only the Wounded Can Forgive: Reading Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov After Betrayal

By: Shreyas Jain

Date: 11/4/23

Eichenberg, Fritz. Illustration from The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky. 1940s, engraving.

Accessed via Russian Art Gallery Blogspot, https://karamazov.tumblr.com

I. The Wound: Where Faith and Suffering Collide

To read Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov after betrayal is to revisit the book not as literature, but as confession. It ceases to be an exploration of ideas and becomes instead a mirror of one’s own ache, where characters are not archetypes but fractured reflections of our deepest contradictions. And nowhere does this mirror cut more sharply than in the lives of Alyosha, Ivan, and Dmitri—each wounded, each a different answer to the same question: what can be done with pain?

Ivan, the rationalist, is perhaps the most obvious stand-in for the modern betrayed soul. He cannot reconcile the existence of suffering with the possibility of a good God, famously refusing his ticket to a paradise purchased by a child's tears. His logic is clean and brutal: if God allows pain, especially innocent pain, then God is guilty. Ivan believes the betrayal is metaphysical. And so, like many who have been hurt, he arms himself with intellect, with irony, and with refusal. He will not forgive, because to forgive would be to acquiesce.

But Ivan's strength is brittle. His descent into madness—his hallucinatory conversation with the devil, his inability to act decisively—suggests that the refusal to forgive does not protect us, but consumes us. Betrayal poisons us most when we attempt to contain it entirely in reason.

Dmitri, by contrast, feels everything. He is the abandoned son, the jealous lover, the near-murderer. He knows the chaos of sin, the spiral of shame. Yet Dmitri begins to change when he stops looking outward and starts descending inward. In prison, he begins to speak of rebirth, of atonement. He believes that his suffering can be used redemptively—that even if he is unjustly condemned, he can still become good. Dmitri is Dostoevsky’s embodiment of the existential crucible: pain as the fire through which the soul is purified. It is in him that we see the faint sketch of the paradox Dostoevsky wants us to wrestle with: sometimes the deepest wrong leads us to the only truth that matters.

And then there is Alyosha, who does not rationalize and does not rage. He simply remains. The innocent monk-in-training, the gentle listener, the bearer of others' suffering. Alyosha is not without his own wounds—he loses his spiritual father, sees his family torn apart—but his response is to stay present. He neither denies the pain nor lets it define him. In this, he is closest to Christ. He does not forgive from a place of moral superiority or stoic detachment, but from communion with the woundedness of the world. He forgives because he is part of the wound.

To read The Brothers Karamazov after betrayal is to begin understanding this: forgiveness is not the denial of injustice. It is the bearing of it. It is a wound worn openly. And only the wounded can forgive.

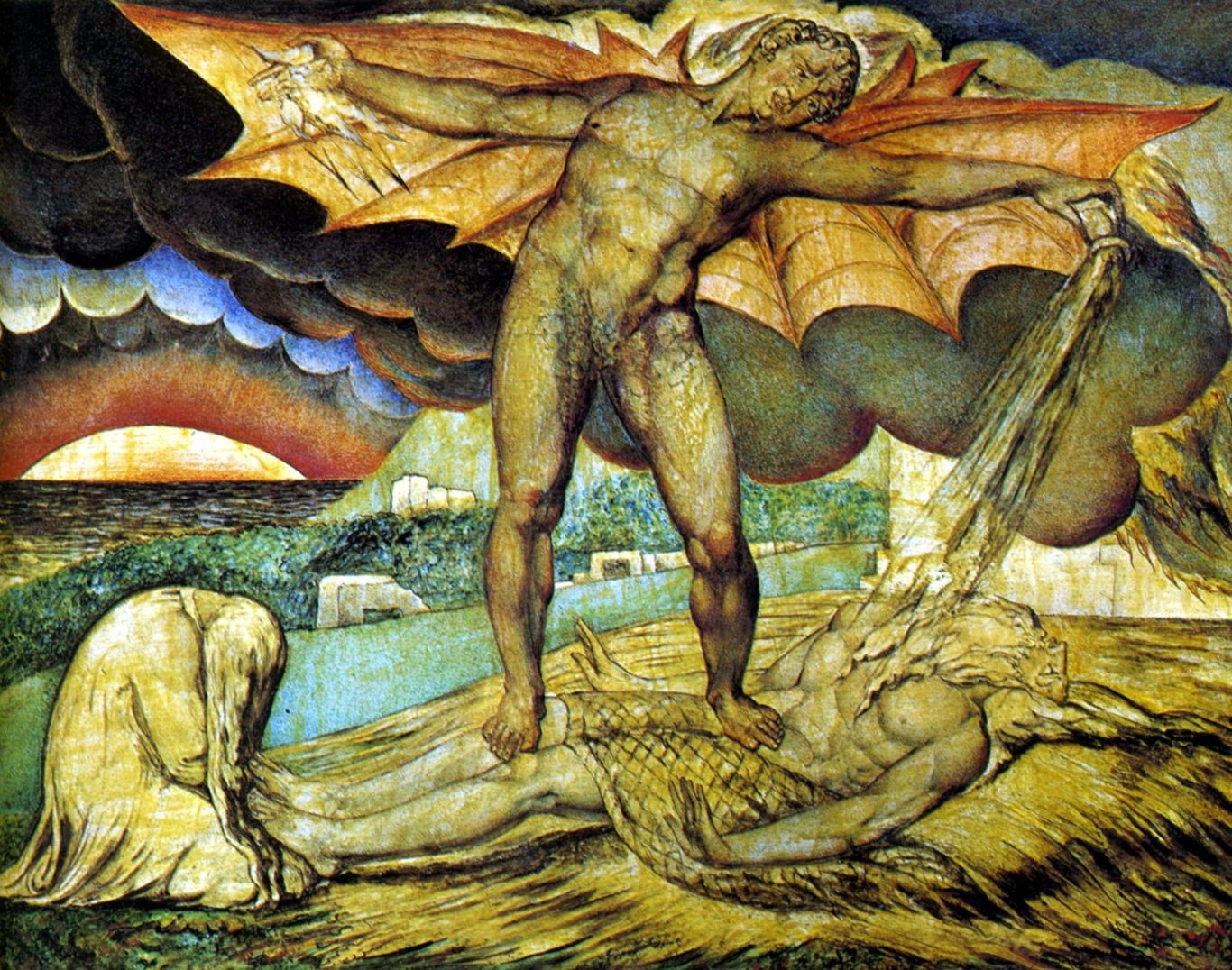

William Blake, Satan Smiting Job with Sore Boils

This image by Blake, from his Illustrations of the Book of Job, evokes the themes of suffering, divine justice, and the human confrontation with evil

II. The Confession: What We Do With Our Betrayers

The most harrowing moments in Dostoevsky's work are not acts of violence but acts of judgment. The Brothers Karamazov forces us to ask not simply how we survive being hurt, but what we will do with those who hurt us. This is not a question of justice in the abstract, but of what kind of people we want to become.

The trial of Dmitri Karamazov is less a legal proceeding and more a spiritual indictment of everyone involved. The prosecution, with its rhetorical flourishes and moral certainty, seems to offer closure. But Dostoevsky makes it clear that the entire courtroom has missed the point. Dmitri may not be guilty of the murder, but he is certainly guilty of other things. And yet the man on trial is not the same man who committed those sins. He has begun to change. The question is: can anyone else see it?

This echoes one of the hardest truths of betrayal: even when someone who hurt us begins to repent, we often want them to stay frozen in their wrongdoing. We prefer our villains unrepentant. It makes our anger feel cleaner. But Dostoevsky complicates this. He insists that people are never just one thing. That goodness and guilt are layered. That judgment without love dehumanizes both the judged and the judge.

Ivan cannot forgive because he cannot see his father as more than a monster. But Dostoevsky invites us to ask: what if Fyodor Pavlovich, repulsive as he is, was also pitiful? What if his cruelty was itself a wound? Forgiveness, then, does not excuse him. It grieves for the deformity of his soul.

Alyosha forgives not by forgetting but by entering into the suffering of the other. He befriends the schoolboys who beat his young friend Ilyusha. He does not demand their repentance before offering them compassion. He acts as if they are more than the sum of their worst actions—and by doing so, he calls them to become something more.

This is where forgiveness, for Dostoevsky, becomes dangerous. It threatens to destabilize the clear boundaries we draw between good and evil, victim and villain. But it also opens the possibility for something greater than justice: grace. And grace, as Dostoevsky shows again and again, is the only thing that can break the cycle of vengeance.

To forgive is not to forget what was done. It is to believe, against all evidence, that the person who betrayed you may yet be redeemed. It is to say, as Christ did, "Father, forgive them; they know not what they do." This is not weakness. It is the highest strength.

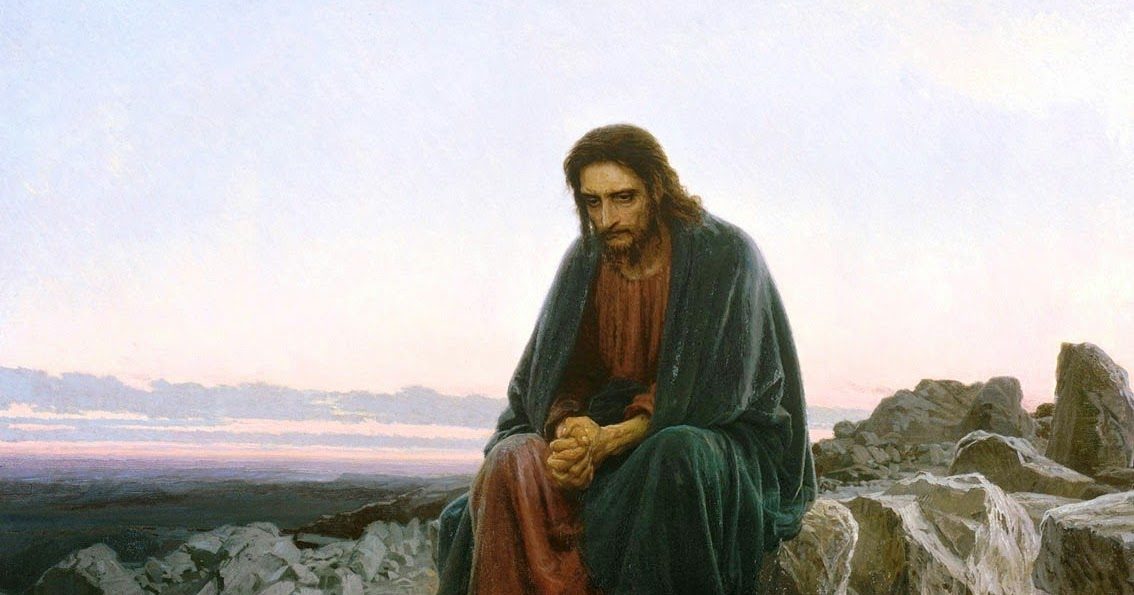

Kramskoi, Ivan. Christ in the Desert. 1872, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Oil on canvas.

aaaaa

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.