Athletics and Adventure

ECNL Soccer - SRFC

I started playing soccer when I was eight — just lunchtime games with friends, nothing formal. One afternoon I came home and asked my dad if I could try it for real. A few weeks later, I was at SRFC tryouts. I started on the lowest team in the club. No shortcuts, no early glory — just years of work. Over four seasons, I climbed through the ranks, eventually reaching NPL and helping lead our team to ECNL — the first squad in SRFC history to do it.

I play center back. It’s a position built on discipline, timing, and trust. You have to be calm when others panic. You organize the line, cover your teammates, and sometimes take the blame so someone else can move forward. I model my play after Virgil van Dijk — composed, physical, and never flustered. And like any proper center back, I follow Liverpool.

One of the high points of my career was traveling to Spain for the Donosti Cup — one of the largest and most competitive international youth tournaments in Europe. Playing against teams from across the world pushed me in new ways. It wasn’t just about skill — it was about adapting, staying composed in unfamiliar situations, and representing my club on a global stage. It made the game bigger, more alive, and reminded me why I fell in love with it in the first place.

Soccer was my first love. It taught me how to suffer well, how to lead quietly, and how to believe in a team even when the scoreboard doesn’t. I hope to play at the college level, not just to keep competing, but to keep growing — because I genuinely became a different, better version of myself out there

Hiking

My earliest hikes weren’t really hikes — I was strapped to my mom’s back, being carried up mountains before I could walk. That’s where it started. Some of my first memories are of dirt trails, pine trees, wind, and sky. Over time, I outgrew the carrier, but the rhythm of hiking stayed with me. It became something we did together — a shared silence, a quiet kind of strength that didn’t need to be talked about.

Now, years later, hiking has become how I reset. It’s where I go when life moves too fast, when things get noisy, when I need to think clearly. Nature has never felt like an escape to me. It’s felt like alignment — a place where things are scaled correctly, where effort means something, and where peace doesn’t have to be earned.

In 2024, I hiked to Everest Base Camp — twelve days of altitude, fatigue, freezing wind, and a sense of awe that’s hard to put into words. Reaching the base of the tallest mountain in the world didn’t feel like a peak. It felt like a beginning. That trip changed the way I understood endurance, and it solidified a dream I’ve carried quietly for years: to one day summit Everest.

Next year, I’ll be hiking the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu, another place layered with history and meaning. Each climb teaches something different — about limits, about pace, about trust in the trail ahead.

Hiking has always grounded me. It’s where I feel closest to the natural world, to the people I’ve shared the trail with, and to something higher than all of it. It’s not just a physical challenge. It’s a way of returning to who I am.

Heading

Heading

aa

Education & Community Service

Leadership Initiatives Advocacy Team Lead

Over the past three years, I’ve led international advocacy teams through the Leadership Initiatives International Internship Program, partnering with local leaders in Bauchi, Nigeria to design and implement community-based solutions to human rights challenges. Alongside close friends Timothy Liu and Brian Ayabe, we worked on two multi-phase campaigns — one targeting child trafficking, the other government corruption. With support from our Nigerian correspondent and domestic team lead, we raised over $1,300 to fund on-the-ground workshops, training materials, and outreach efforts across Bauchi.

Our “SafeKids Nigeria” Child Trafficking Workshop was designed to equip local children with tools to recognize danger, speak up, and protect themselves. Through interactive storytelling, scenario-based role-play, and creative expression (drawing, short skits), we created a space that felt safe and empowering. We also provided resources on how to seek help and connected youth with local protection agencies — embedding the message not just in awareness, but in action.

Our second major initiative — “Say No to Corruption: Building a Better Bauchi Together” — targeted public perception around bribery, favoritism, and civic dishonesty. We intentionally made the workshop personal and accessible, using humor, games, and shared stories to show that corruption isn’t an abstract force — it’s something that shapes everyday life. Participants role-played situations like job favoritism or bribery in schools and took pledges to reject unethical behavior in their own lives. We wanted to change behavior, but first, we had to change what people saw as problematic. That was the real challenge — and the real work.

Across both campaigns, we reached over 300 participants, and what stayed with me wasn’t just the success of the workshops — it was the realization that reform doesn’t begin with institutions. It begins with imagination, with reshaping what people believe they’re allowed to expect from their leaders and communities.

This experience sharpened every part of me: research, public speaking, cultural humility, real-world project management. More importantly, it deepened my commitment to pursuing legal reform not just in policy — but in hearts, expectations, and lived reality.

Project Info:

92e62f9f-3db8-4786-b331-5b31090d26e1

329a9438-baa6-44c3-8e0c-86016571be1e

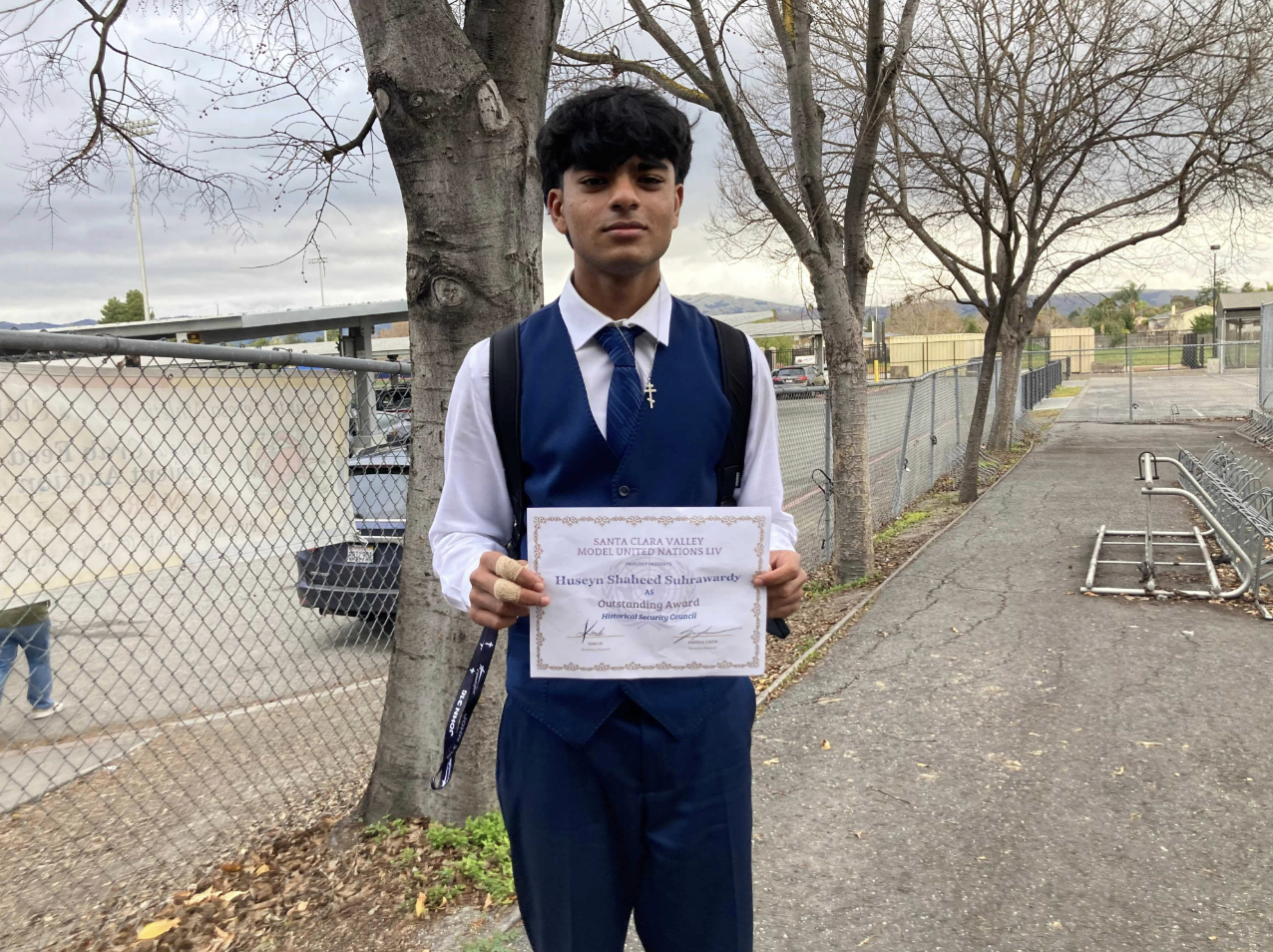

Model United Nations Co-President

For the past four years, Model United Nations has been one of the most formative parts of my academic life. I began as a delegate learning the ropes of international diplomacy, and soon found myself stepping into leadership. For three years, I served as Education Officer, where I mentored new delegates — not just in resolution writing and parliamentary procedure, but in the deeper skills that MUN demands: critical thinking, negotiation, presence under pressure. I built weekly training modules, ran mock committees, and helped develop the crisis team that eventually became one of the most respected programs at our school.

This year, I serve as Co-President of Quarry Lane’s MUN program, leading both logistics and training for our growing delegation. Along the way, I’ve earned recognition as Outstanding Delegate at SCVMUN and Best Delegate at QLMUNC, but more than awards, MUN has sharpened my understanding of diplomacy as a kind of leadership rooted in listening — in balancing idealism with pragmatism, advocacy with restraint. It’s taught me how to speak with clarity, to think on my feet, and to hold my ground when ideas are tested. More importantly, it has shown me that real change — whether in debate or in the world — starts with how well you understand those who disagree with you.

Heading

Heading

aa

Georgetown Law Intensive

In the summer of 2023, I participated in Georgetown University’s Law & Advocacy Program, where I worked alongside public defenders, law professors, and returning citizens on issues rooted in real criminal cases and legislative reform. My team supported the defense in an active trial involving a concealed carry charge — specifically, whether a licensed firearm was “entirely hidden from public view,” as required by D.C. law. We examined the scope of public view using both local precedent and comparative foreign case law from the Supreme Court of India, building an argument that the officer’s non-routine vehicle inspection placed the event outside what is legally considered public view. Our defense drew from a 2008 New Delhi Supreme Court ruling on caste-based hate speech — applying it via 28 U.S. Code § 2467 (enforcement of foreign judgments) to broaden our interpretive reasoning.

Beyond casework, I helped draft and advocate for the H.E.L.P. Act (Human Emergency Logistics Program Act) — federal legislation designed to expand access to mental health and reentry services through the 211 and 988 emergency systems. We briefed congressional offices, met with lawmakers, and presented data showing the disproportionate risks faced by people with untreated mental illness during police encounters.

Throughout the program, I was mentored by Brandi Harden, a leading criminal defense attorney and adjunct professor at Howard and American University. Under her guidance, I learned not just legal strategy, but how to listen — to witnesses, to clients, and to the silences that often hide injustice. She taught me that good lawyering isn’t about dominating a courtroom. It’s about clarity, care, and conviction.

This experience reshaped how I understand justice. I grew as an advocate, but more importantly, I grew in patience, in empathy, and in the belief that the law — if held rightly — can still be used to restore what’s been broken.

Community Reading Buddies

At Community Reading Buddies (CRB), I mentored elementary school students from underserved Oakland communities to help improve their reading skills and build confidence in literacy. Through weekly one-on-one sessions, I developed meaningful relationships with my mentees, tailoring support to their pace and personality. The work demanded patience, empathy, and consistency — not just to teach reading, but to model presence and encouragement. Over time, I saw measurable growth not just in their fluency, but in their willingness to try, speak up, and believe in their voice.

Heading

Heading

aa

Hobbies!

Writing, Philosophy, and Theology

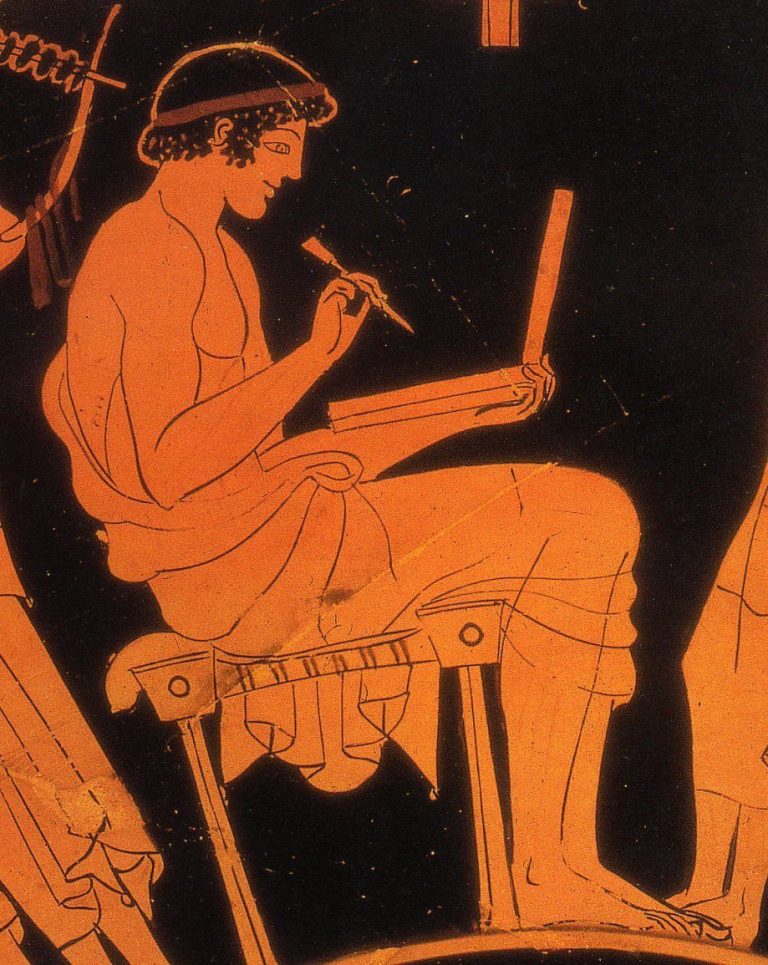

Writing has always been more than a skill for me — it’s a way of thinking clearly, of making meaning from complexity. In a world that often underestimates writing as secondary to speech or performance, I’ve found it to be the most honest place to test ideas, to question myself, and to try, quietly, to say something true.

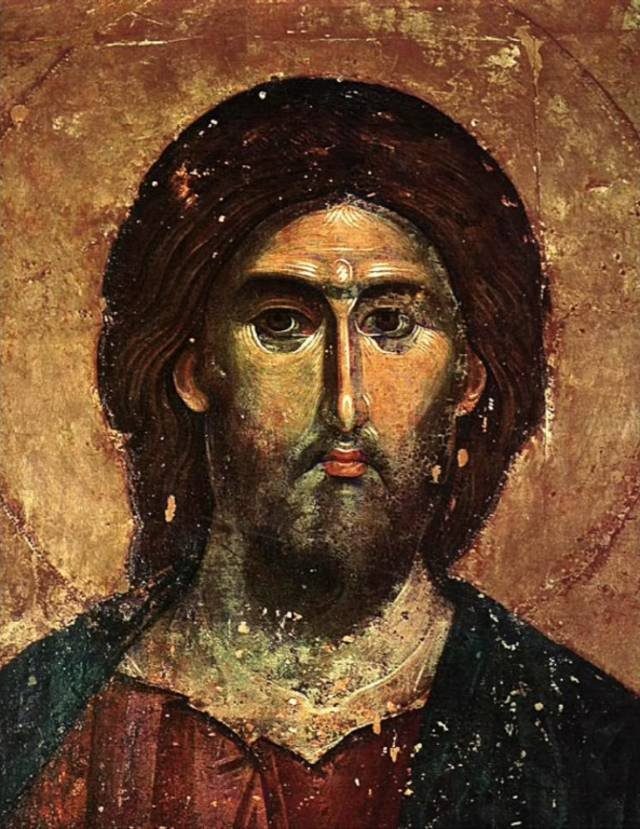

Much of my writing has centered on history, law, theology, and power — and how the ideas that shape civilizations rarely begin in legislation, but in belief. Through a series of long-form essays, I’ve explored topics like the ethics of preemptive war, the problem of evil and the necessity of law, and how Orthodox Christianity heals a fragmented imagination through liturgy, silence, and beauty. These pieces weren’t written to prove anything. They were written to wrestle — with language, with tradition, and with the questions that don’t go away just because they’re hard.

Philosophy sits at the center of how I approach every other discipline. The moment we try to say anything about the world — that something is just, or real, or knowable — we are already standing on metaphysical ground. Even logic itself only holds meaning if we accept certain first principles, which are neither scientific nor visible. They are inherited, intuited, or revealed — and all of that puts us squarely in the domain of philosophy and, eventually, theology.

I study theology not as a field of facts, but as a path. Orthodox Christianity, in particular, has taught me that faith is not an argument to be won, but a mystery to enter. And that the mind’s highest calling isn’t to master truth, but to bow before it.

Writing has given me a language to explore those mysteries — not to solve them, but to dwell in them with care.

Star Wars and Lego

Star Wars is something I keep coming back to , not just because of the action or the world, building, but because it’s way more philosophical than people give it credit for. It’s not some black-and-white story about good vs. evil. The Jedi aren’t perfect. The Sith aren’t purely monsters. Both sides are flawed, and part of what makes the story interesting is figuring out who you actually relate to, who’s really trying to live with pain, with discipline, with failure. My favorite character, hands down, is Darth Maul. Not because he’s cool, though he is, but because he’s tragic. He was created by Palpatine to be a weapon, nothing more. Then he’s discarded, literally cut in half and forgotten. And what does he do? He claws his way back, piece by piece, desperately trying to earn the approval of the man who broke him. He becomes more than just angry, he becomes desperate, obsessed. That’s not just villainy, it’s heartbreak. And that’s what makes Star Wars stick with me. The more you watch, the more you realize every character is carrying something heavy. The universe keeps expanding, and there’s always another layer to dig into. Sometimes I honestly think it’s more complex than real history.

LEGO’s been a part of my life for as long as I can remember. It started with small sets, but pretty quickly I got into the big ones — the huge Star Wars ships, buildings with thousands of pieces, sets that took hours, sometimes days. I could sit for hours building, taking things apart, putting them back together. There’s something really calming about it. It’s structured, but creative. You have instructions, but you’re still solving problems, still thinking. It’s one of the few things that lets me completely tune out the noise — no pressure, no deadlines, just focus. Some people meditate — I build. And I’ve probably spent way too much time and money on it, but I honestly don’t care. There’s a sense of pride when you finish something massive and it all clicks together — and sometimes, I’ll take it apart and start again. That’s what I love about LEGO: you can break things and rebuild them better.

Heading

Heading

aa

aaaaa

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.