"And the Son": A Creed, a Clause, and the Collapse of Christian Unity

By: Shreyas Jain

05/04/2025

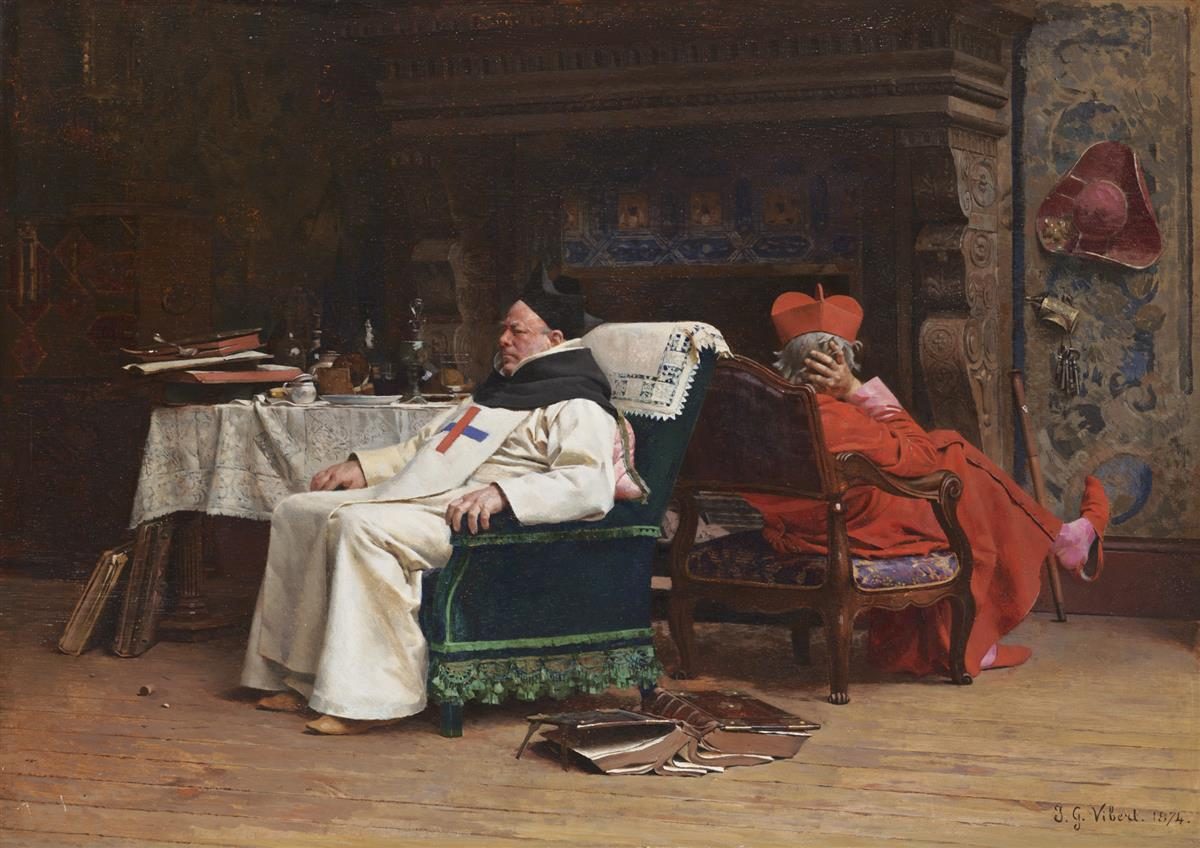

Vibert, Jehan Georges. The Schism. 1874, oil on canvas, private collection. Accessed 05/04/2025, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jehan_Georges_Vibert_-_The_Schism,_1874.jpg.

Introduction

Few single words in the history of Christianity have carried as much weight, or wrought as much division, as the Latin term Filioque. Added quietly in the forests of Visigothic Spain, “and the Son” would ignite a theological wildfire that smoldered for centuries. At the heart of this controversy lies a deceptively technical question: Does the Holy Spirit proceed from the Father alone, or the Father and the Son? For many in the Latin West, the addition was a necessary clarification. For the Greek East, it was an affront to tradition and Church authority. Both sides foresaw trouble, but neither understood what it would mean for the future of Christendom.

Historical and Doctrinal Background

The East-West Schism of 1054 has its historical and theological origins in the very establishment of Christian orthodoxy and the Nicene Creed at its center. Initiated in 325 AD through the patronage of Emperor Constantine at the Council of Nicea, the creed was instituted in response to Arianism, a heresy claiming Christ was of a different substance (homousis) from the Father, The creed was supplemented in its expanded form in 381 AD through the First Council of Constantinople to include statements about the Holy Spirit stating He “proceeds from the Father,” a description based on John 15:26: “When the Advocate comes, whom I will send to you from the Father - the Spirit of truth who goes out from the Father - what he hears he will declare to you.”

From its very beginning, creed was meant to be a doctrine anchor and a tool of ecclesiastical unity throughout the Roman Empire. That a religious formula articulated in imperial synods was so important is a measure of how firmly church and state were intertwined in late antiquity. The creed was more than a profession of faith; it was a token of orthodoxy and a product of the imperial will. Sounding disagreeable to it was heretical and even treasonous. This formalized theology expressed and sustained a vision of a Church united in apostolic succession and communal sacramental life. Fissures began to emerge even in this early phase. Linguistic differences between Greek-speaking East and Latin-speaking West already raised obstacles to the theological consensus. Doctrinal terms frequently have no exact counterparts in the other language, and so subtly but importantly differed in meaning. The Latin “substantia” and Greek “ousia” both seek to express “essence” or “substance,” but with differing connotations in their different philosophical traditions.

Such early semantic tensions deepened in sophistication as the Eastern Christian theology became more mature. The Cappadocian Fathers - namely, Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus - promulgated a Trinitarian theology fronted by a Father monarchy from whom both the Son is begotten and the Holy Spirit proceeds. This framework was designed the uphold both unity and personal individuality of each hypostasis in the Trinity. The procession of the Spirit only from the Father exceeded mere doctrine and was instead a necessary consequence of Eastern stress on the Father as a singular source in the Godhead. In Western theology, however, things went a different way. Saint Augustine of Hippo (5th Century AD) built a psychological model of the Trinity based on the relational dynamics between the three hypostases. In De Trinitate, he argued that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the mutual love (communio) between the Father and Son. Though Foloioque is not used in Augustine’s terminology in a clear manner, it is in the conceptual foundation he provided that Western theology would later make a case for its inclusion in the Creed.

The difference between Eastern and Western paradigms of technology, of monarchical vs relational, might have remained a matter of relative emphasis were it not for the growing tension between Roman and Byzantine ecclesiastical poles. As Roman Imperial Unity disintegrated, particularly in response to the sacking of Rome in 410 and the fall of the Western Empire in 476, Roman Bishops became a chief figure of stability and influence in the West. The Byzantine Church continued to be associated with Constantinopolitan Imperial Authority and evolved a more conciliar model of church governance. This difference in ecclesial form and political affiliation carried with it doctrinal consequences. The West’s increasing concentration of papal supremacy and centralized theology gave it more and more ease in asserting and formalizing developments in doctrine independently, whereas the East remained firm in its insistence on ecumenical councils as the only means of creedal definition.

The conflict boiled over in 589 AD at the Third Council of Toledo, a regional council held in Spain. It was there that the Filioque addition was inserted into the Creed, stating that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son. The Filioque was introduced in an effort to suppress remnant Arianism by declaring full divinity and equal station for the Son with the Father. Well-intentioned on a pastoral level, however, this addition was never sanctioned by any ecumenical council and was instituted ad hoc. Over the ensuing centuries, it gradually took root in the Latin Church, especially in the course of the Carolingian Renaissance, when it tried to integrate and uniform Western liturgical and theological images. By the 9th century, Filioque was a flashpoint in theology and politics. The East was objecting to both the meaning of the clause and to how it was inserted, unilaterally without the concurrence of the universal Church. This was seen to be a violation of coniliar tradition and ecclesiastical propriety. In short, the Filiioque dogmatic conflict was not just a spontaneous eruption. Rather, it was a product of centuries of divergent theology, linguistic confusion, and ecclesiastical competition.

Filioque in Depth

While the historical background reveals how the Filioque emerged, its embedded theological dynamism and contested reception across Christendom demand closer scrutiny. The Latin West accepted Filioque with more theological assurance in the course of the 8th and 8th centuries, but acceptance was contentious, even inside the Western Church. Pope Leo III, in early ninth-century writing, most notably objected to changing the creed text even though he concurred with the doctrine itself. The Liber Pontificalis reports that Leo ordered two silver shields inscribed with the original Greek and Latin redactions of the Nicene Creed (excluding Filioque) and had them hung at Saint Peter’s Basilica. His purpose was unmistakable: to maintain ecumenical solidarity by retaining the conciliar form even while sharing sympathies with whatever theological impulse prompted the addition. The example of Leo shows us that the dispute was about more than East vs. West, and was also internal to Western discussions regarding creedal legitimacy.

The Western theological explanation for Filioque leaned considerably on the Augustinian terminology but was only formalized in response to Frankish pressure. The Carolingian court, particularly Charlemagne’s court, was a galvanizing factor in making the Filioque dogma official. Western clergy in The Libri Carolini prompted a double-procession model of the Spirit in an effort to distinguish Frankish orthodoxy from Byzantine Christology and to signal independence in theology from the Eastern Church. A. Edward Siecienski frames this as a turning point when theology and empire became intertwined” “What had been a local addition gradually became a badge of Latin theological identity” (Siecienski, 2010, p, 103).

The East responded with a powerful intellectual and ecclesiological counter-offensive. Patriarch Photius of Constantinople in 867 AD sent out an encyclical to Eastern patriarchs, condemning the Latin Filioque as a heretical innovation. For Photios, it was a matter of compromising the Father’s monarchy and creating confusion about the Spirit’s origin to add and the Son. His language was polemical but based on a refined Trinitarian theology. “It is blasphemy… to suppose a double cause of the Spirit’s existence.” For Photius and those who followed in his tradition, this was not about hairsplitting over theology but preserving the integrity of divine revelation. The acuteness of Photius’ denunciation indicated how fully Filioque was a lightning rod for larger tensions. These would include ecclesial autonomy, biblical exegesis, and where doctrine was to be located. It is interesting to consider how the Eastern objection went beyond substance. The manner of insertion, unilateral and unauthorized by an ecumenical synod, was as galling as the doctrine. The canon law of the Council of Ephesus (431 AD) specifically prohibited any “composition of another faith,” and the Eastern Church saw Filioque to be an attempt to do exactly that.

Complicating matters was that Eastern responses to theology were also varied. Saint John of Damascus, although earlier than the heart of the dispute, expressed in An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith this idea: that the Spirit “proceeds from the Father” and is “sent through the Son.” This nuance between procession and mission would be a main point of the Orthodox argument to distinguish between eternal origin and temporal sending. This was long on most Latin theologians, who identified the Spirit's economic sending with ontological procession. Later, Bishop Kallistos Ware said of it: “Many of the arguments stem not from dogmatic difference but from differing conceptual categories and linguistic limitations” (Ware, 1997, p.218). In contrast to this, Western thinkers were more concerned to assert the integrity of the Godhead to avoid what was seen to be a tendency towards subordinationism. Jaroslav Pelikan, an American scholar of the history of Christianity, Christian theology, and medieval intellectual history at Yale University, observes that it was not in a desire to undermine Eastern theology but to protect the Son’s equality with the Father in response to persistent Arian opposition: “The insertion was not aimed at East-West division, but at preserving the Nicene confession in a hostile theological climate” (Pelikan, 1975, p. 137).

Nonetheless, the theological gulf was deepened by liturgical and pastoral reinforcement. The Filioque was asserted, yes; it was also sung. Liturgical repetition in Western culture institutionalized the phrase in public perception and made it impossible to envisage removing it. This divergence between both Churches reached a symbolic and literal crossroads when Western missionaries, particularly those in Bulgaria and Moravia during the 9th century, brought the Filioque-laden creed to newly converted Slavic regions. Byzantium saw these missionaries are undermining their jurisdiction and spreading “innovations” on Eastern soil. In this sense, Filioque functioned not only as a doctrinal symbol but as a geo-theological weapon in the competition for Christendom’s margins.

Below surface level disagreements over doctrine was incompatibility of Church structure and differing claims to Authority regarding how each faction went about resolving questions of doctrine. In the east, power was shared among the five patriarchates of Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem in a form called the pentarchy. Though there was a premise of honor for Rome, decisions on doctrine were to be made by the concurrence of Bishops in ecumenical councils. The Eastern model was synodal in nature inasmuch as it was a collegial approach based on apostolic precedent and continually substantiated by early councils’ canons.

In contrast to this arrangement, the Western Church, deprived of an emperor following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476, tended to consolidate power in the Bishop of Rome. The Roman pontiff gradually went from being a primus inter pares, first among equals, to assuming religious jurisdiction over all Christians. This process gained momentum in the Carolingian., especially in Charlemagne. Charlemagne's coronation in 800 AD by Pope Leo III as "emperor of the Romans” without seeking approval in Constantinople was a contentious move that symbolically broke Western Christendom away from Byzantine jurisdiction.

This newly formed alliance between the Frankish court and the papacy provided both military security and theological assertiveness to Rome. It also enabled the Western church to foster a unique imperial theology - imperial theology that would legitimize the increasing influence of the papacy as spiritually independent and superior to any individual emperor. Historian Steven Runciman states this coronation was “a turning point at which the West no longer considered itself bound to share in the political or ecclesiastical structure of the East” (Runciman, 1955, p.34). This break not only devalued Byzantine imperial prestige but also delegitimized the Cooperative model of ecclesial authority continued in use in the East.

These rivalries soon spilled over into missionary territories whose stakes were more tactical than theological. During the 9th century, contesting the conversion of the Slavs fueled tensions between Constantinople and Rome. When both sides sent in missionaries to Bulgaria, they carried with them not only different rites but also competing ecclesiastical claims. Patriarch Photius once again confronted these incursions straight on. In his 867 AD encyclical to Eastern patriarchs, he censured the Latin missionaries for bringing foreign practices to canonically Eastern territories. Photius penned: “They try to destroy what has been established by the Fathers, to take away other people's flocks and to form a faith not professed in any synod.” His statement bolsters the sense that in pursuing these actions, Rome was behaving in both a heterodox manner and an imperialistic one.

These tensions were exacerbated by the structural evolution of the papacy itself. By the 11th century, the Gregorian reform movement had redefined the papacy's role even further. Reformers such as Pope Gregory VII asserted the Pope's right to depose secular rulers, enforce clerical celibacy, and regulate all aspects of Church governance. The 1075 Dictatus Papae, issued two decades after the schism, declared that the Roman pontiff alone could make new laws, convene councils, and be judged by no one. Though this document post-dates 1054, it reflects a long development trajectory of centralization and absolutism within Latin ecclesiology. This was contrasted sharply with the Eastern model, in which none of its Bishops or even its patriarch of Constantinople was solely authorized to revise doctrine or practice. The Eastern Church viewed itself as the guardian of an undistorted tradition of the early Church in which local communities operated autonomously but with oversight by conciliar authority. Any amendment to a communal Creed or liturgy in the absence of a concurrence of all pan-Orthodox authorities was not only irregular but also illegitimate.

Cultural and Other Theological Disputes

The Filioque dispute overshadowed all of the disagreements dividing East and West, but was not its only source: rather, it was part of a set of interlocking and pastorally devastating disputes, which together had long since undermined the basis for ecclesial unity. Yet these were just the kind of disputes that the disagreement over clerical discipline in sacramental practice, as well as different cultural and theological worldviews, which also had some caloric value for the great schism of 1054 itself, were made of. They built an environment where the insertion of a single word into a creed could cause a complete ecclesial break. One of the most noticeable divergences was the increase in liturgical practices. The Orient, a region profoundly marked by the Byzantine aesthetic and mystical theology, possessed a liturgy that stressed transcendence, theosis (deification), and an effective sacramental presence. This liturgy, performed to this day as the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom, is highly symbolic, flavored with incense and chant, and its rich iconography. Western liturgy, on the other hand, at least since the standardization of the Roman right under Charlemagne, was characterized by sober ceremonialism, more and more judicial language, less and less of the sensory. Ware writes that the West came to describe the Eucharist in more legal and academic terms, more emphasis being placed on transubstantiation and atonement rather than on broader ideas of the divine mystery and the effect on the faithful (Ware, The Orthodox Church, 1997, pp.223-225).

This kind of theological subtlety got expressed in the bread of the Eucharist. The Latin Church employed the use of unleavened bread as in Jewish Passover usage, which became a Lenten food in place of leavened foods. The Greeks adopted leavened breads, which they felt would be a better symbol for the risen Christ and the life in all its fullness that he brings. Scored initially as a disparity of church usage, the East perceived the West's deployment of unleavened bread (azymes) to be doctrinally deficient and symbolically barren. The mid-11th-century council initiated by Patriarch Michael Cerularius ruled that only the bread offered in the Divine Liturgy could be used as Eucharist and condemned the use of azymes as evidence of deviation from Apostolic tradition by the Latins. Another, less tangible barrier was the language itself. By the 9th century, these two churches were virtually talking past one another, in the literal sense of the phrase. It had long been neglected in the West, and Latin was a strange tongue to most Eastern ecclesiastics. Assertive creeds (substantia, persona, or homoousios, say) often did not translate readily, leading only to a minefield of misleading terminology. Theological misunderstanding John Meyendorff emphasizes that this shift of language caused a great misunderstanding theologically. For example, the Latin procedere and the Greek ekporeusis are both translated “proceeds” in English, but procedere includes relational emanation, which ekporeusis does not; rather, it is simply origin in a single source (Meyendorff, Byzantine Theology, 1979, pp. 78-80).

The estrangement was also furthered by clerical practices. In the East, married men could be ordained as priests, although bishops were selected from the celibate monastic ranks. In the West, following the Gregorian reforms, clerical celibacy became mandatory. This was out of a theological concern for purity and a political strategy to sever hereditary claims to church property. The East viewed this as an unnecessary and unbiblical imposition. More broadly, the role of monasticism differed starkly. In Byzantium, monks were seen as both ascetics and theologians, and their authority could sometimes surpass that of bishops. In the Latin Church, monasticism, especially under Benedictine rule, was more institutionally ordered and integrated into hierarchical structures. These differences pointed to a more foundational divergence in theological method. Eastern theology was apophatic and experiential, drawing heavily from the mystical tradition of the Desert Fathers and the writings of figures like Maximus the Confessor. Western theology, by contrast, increasingly pursued a cataphatic, analytical approach (something that would eventually form into scholasticism). The disparity would fully bloom in the works of Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century, but the seeds were already present centuries earlier. The East’s suspicion of systematic theology, what it often regarded as Western rationalism, was not an aesthetic preference but a reflection of its view that divine truth transcends human comprehension.

Even the calendar became a point of friction. The West adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1582, while the East remained on the Julian calendar. Though this event occurred long after the schism, it epitomized a pattern: Rome changed and Constantinople resisted. What is notable is that no single disagreement-not - not bread, not language, not celibacy-was by itself enough to cause a rupture. But taken together, these differences constructed a cultural and theological architecture that made unity fragile and division increasingly likely. As the Easter Church saw it, the West had not simply taken another path, it was actively rewriting the faith, both in practice and in principle. Meanwhile, the West increasingly saw the East as obstinate, unwilling to evolve with the needs of the Christian world.

These cultural and theological tensions did not fade in the decades leading up to 1054. On the Contrary, they became more pronounced. The cumulative effects of these divergences were a slow-burning alienation that primed both sides for confrontation. When the flashpoint finally came, with bulls of excommunication traded in Constantinople, it did not erupt in a vacuum. It exploded across a landscape already fragmented by mutual incomprehension. And yet, by 1054, neither side viewed the events as an irrevocable schism. The immediate diplomatic fallout appeared resolvable, even temporary. In reality, the infrastructure of unity had already crumbled. The remaining sections of this essay will turn to the events of that fateful year and explain why the Filioque, amid all this, became the symbolic and functional wedge between East and West.

The Events of the Schism in Depth

The excommunications that marked the formal schism occurred not during a doctrinal council, but as a finale to a collapsed negotiation between two estranged religious bodies. The moment itself was abrupt; the rift it revealed, centuries in the making. In the Spring of 1054, Pope Leo IX dispatched a delegation to Constantinople led by Cardinal Humbert of Silva Candida. The goal of this legation was officially to mend relations with the Eastern Church following disputes over liturgical practice in southern Italy. The territory had recently come under Norman rule and papal influence, but had traditionally used the Byzantine rite. The Eastern Patriarch, Michael Cerularius, had closed Latin churches in Constantinople and denounced Latin practices, making the work of the delegation more than urgent. Cardinal Humbert arrived in Constantinople with a letter from the Pope, the Responsa ad Capitula Michaelis, which laid out grievances against Cerularius and asserted the primacy of the Roman see. The language was combative. In one passage, Leo cited the forged Donation of Constantine, a now-debunked document claiming the Emperor Constantine had granted temporal and spiritual authority over the entire Church to the Bishop of Rome. The Pope wrote: “The holy Roman Church has been placed above all others by the word of our Lord and Saviour” (Responsa, 1054). While many of the issues were ostensibly ecclesiological, the presence of the Filioque in Humbert’s list of charges reminded all involved that theological divergence was never far from the surface. Cerularius rejected both the tone and the claims, refusing to meet with the delegation directly.

The impasse culminated in an act of theatrical provocation. On Saturday, July 16, 1054, during the Divine Liturgy at the Hagia Sophia, Constantinople’s most sacred basilica, Cardinal Humbert marched up the altar and placed a bull of excommunication against Cerularius on it. The document accused the Patriarch of heresy, including omitting the Filioque and allowing married priests. It declared: “Let him be anathema, Maranatha, with all his accomplices and all those who hold communion with him” (Bull of Excommunication, 1054). Humbert and his entourage then left the city without further negotiation. Cerularius responded with a synod and issued a counter-excommunication of the Roman legates. While Humbert’s bull had been issued after Pope Leo IX had died (on April 19, 1054), making it technically invalid under canon law, it still had profound symbolic force. Cerularius’ reply accused the Latins of heresy for their liturgical practices and refusal to adhere to conciliar governance. In his official reply to the Patriarchs of the East, Cerularius condemned “the arrogance of the Latines and their uncanonical customs” (Letter to Peter of Antioch, 1054).

Interestingly, at this point, there was no explicit declaration of a permanent schism, and neither side convened a council to ratify the split. This ambiguity lingered: ecclesiastical correspondence between the two churches continued sporadically, and formal condemnation of each other’s ecclesiastical orders did not occur. However, as A. Edward Siecienski notes, “the 1054 exchange revealed that neither side had a functioning theological or institutional mechanism to restore unity” (Siecienski, 2010, p.153). Contemporary observers were largely silent on the schism’s immediate consequences, which only supports how incremental the break truly was. The Chronographia of Michael Psellos, a Byzantine intellectual and courtier, only briefly alluded to the incident, more interested in the court politics than church disputes. In the West, chroniclers like Peter Damian mentioned the legation but did not frame it as the end of unity. The sense of a definitive breach developed retrospectively as the entrenchments hardened over the next two centuries. Nevertheless, the 1054 incident institutionalized estrangement. Latin missionaries were barred from Easter territories. Eastern Christians traveling west often found themselves isolated or condemned. Communion between the two churches effectively ceased, not by dogmatic pronouncement but by practice. As Jaroslav Pelikan observed, “schisms become permanent not through declarations, but when people cease acting as if they belong to the same Church” (Pelikan, The Spirit of Eastern Christendom, p. 201).

Conclusion

The addition of the Filioque clause did not single-handedly rupture Christian unity, but it was the theological flashpoint through which deeper fault lines- political, cultural, and doctrinal -were exposed. When unity finally broke in 1054, Filioque stood as a cipher: a small phrase that embodied centuries of separation. The schism, once realized, proved less a split than a final acknowledgement of how far the churches had already drifted apart.

References (APA) OR Works Cited (MLA)

Aquilina, Mike. The Fathers of the Church: An Introduction to the First Christian Teachers. Our Sunday Visitor, 2006.

Augustine of Hippo. On the Trinity (De Trinitate). Translated by Arthur West Haddan, New Advent, www.newadvent.org/fathers/1301.htm. Accessed 10 Mar. 2025.

Bettenson, Henry, and Chris Maunder, editors. Documents of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Catholicus. “The Third Council of Toledo (589 AD): The Conversion of the Visigoths and Spain’s Catholic Destiny.” Catholicus.eu, https://catholicus.eu/en/the-third-council-of-toledo-589-ad-the-conversion-of-the-visigoths-and-spains-catholic-destiny/?pdf=2813. Accessed 12 Mar. 2025.

Council of Toledo. “Third Council of Toledo (589).” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_Council_of_Toledo. Accessed 12 Mar. 2025.

Damascus, Saint John of. An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith. Translated by Edwin Hamilton Gifford, Eerdmans, 1958.

Meyendorff, John. Byzantine Theology: Historical Trends and Doctrinal Themes. Fordham University Press, 1979.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. “The Filioque: A Church-Dividing Issue?” Theology Today, vol. 32, no. 2, 1975, pp. 132–144.

Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Spirit of Eastern Christendom (600–1700). University of Chicago Press, 1974.

Photius of Constantinople. “Encyclical to the Eastern Patriarchs (867 AD).” In Documents of the Christian Church, edited by Henry Bettenson and Chris Maunder, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 65–67.

Photius of Constantinople. “Letter to Peter of Antioch (1054).” In Documents of the Christian Church, edited by Henry Bettenson and Chris Maunder, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 67–68.

Psellos, Michael. Chronographia. Translated by E.R.A. Sewter, Yale University Press, 1953.

Runciman, Steven. The Eastern Schism: A Study of the Papacy and the Eastern Churches during the XIth and XIIth Centuries. Clarendon Press, 1955.

Siecienski, A. Edward. The Filioque: History of a Doctrinal Controversy. Oxford University Press, 2010.

“Text of the Nicene Creed (325 AD).” Christ the Savior Orthodox Church, https://christthesavioroca.org/files/2020-Resurrection-Classes/The-Nicene-Creed-of-325.pdf. Accessed 8 Mar. 2025.

“Text of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed (381 AD).” Promise686, https://www.promise686.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Nicene-Creed.pdf. Accessed 8 Mar. 2025.

University of California Press. “Letter of Pope Leo IX to Michael Cerularius (Responsa ad Capitula Michaelis).” In The Church in the Age of Feudalism, https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft009nb09t&chunk.id=d0e2831&toc.depth=1&toc.id=d0e2831&brand=ucpress. Accessed 13 Mar. 2025.

Ware, Timothy (Bishop Kallistos). The Orthodox Church. Penguin Books, 1997.

aaaaa

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.