Faith and Force: How Religion Shaped Medieval Warfare

By: Shreyas Jain

Date: 11/4/23

Signol, Émile. Taking of Jerusalem by the Crusaders, 15 July 1099. 1847, Musée du Château de Versailles, Versailles, France

Men prayed before battle, but they did not always pray for peace. They prayed for victory, for vengeance, for the triumph of their God over the gods of others. In blood and iron, they believed they were writing a higher story — one where killing could be sanctified, and death could be a doorway to salvation.

To march into battle was to step into a battlefield shaped not only by kings and lords, but by preachers, monks, and popes. War was not merely permitted; it was commanded. Not merely regretted; it was celebrated.

I. The Baptism of the Sword

The fusion of faith and violence can be traced as early as the reign of Charlemagne (r. 768–814).

Charlemagne’s campaigns against the Saxons, chronicled by the monk Einhard in the Vita Karoli Magni, were framed not merely as territorial expansions, but as holy wars — wars to convert the pagan Saxons to Christianity by force if necessary.

Einhard records how Charlemagne, after years of resistance, imposed baptism on the Saxons en masse under threat of execution. The Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae (782) demanded death for any Saxon who refused Christian baptism.

It was an early and brutal declaration: the sword and the cross would advance together.

In this period, mass conversions and military subjugation were not contradictory but seen as complementary acts.

Faith was not simply preached; it was enforced.

Law codes and religious identity fused into a single demand for allegiance — to king, to creed, to cross.

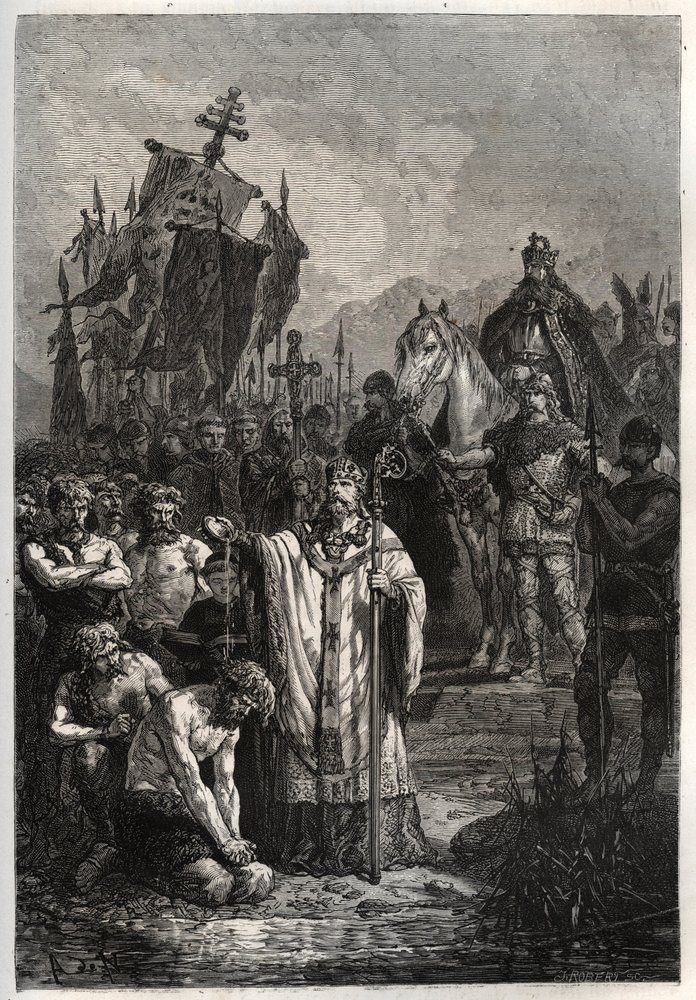

French School. Baptism of the Pagan Saxon Leader Widukind under the Pressure of the Emperor Charlemagne. c. 19th century, engraving

II. The Crusades: Sanctifying the Battlefield

No moment captures the collision of faith and force more vividly than the Crusades.

When Pope Urban II called the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont in 1095, he declared: "Deus vult" — God wills it.

He promised absolution to those who took up the cross and fought to reclaim Jerusalem from Muslim rule. The battlefield was now sanctified ground. War became an act of penance.

The Gesta Francorum, a chronicle written by an anonymous crusader, records the terrifying zeal that Urban’s message unleashed.

Knights and peasants alike sewed crosses onto their garments, abandoning homes and families to march toward a distant, half-imagined Holy Land.

The religious character of these campaigns transformed how war was fought:

Crusaders viewed themselves not as mercenaries or adventurers, but as pilgrims with swords.

Battles were often preceded by religious ceremonies, masses, blessings of arms.

Siege warfare (e.g., at Jerusalem in 1099) was punctuated by prayers, processions, and appeals to divine intervention.

The slaughter that followed — most infamously at Jerusalem, where contemporary sources like Raymond of Aguilers described rivers of blood in the streets — was seen not as a violation of faith, but as its fulfillment.

Religion did not moderate violence in the Crusades. It intensified it. It clothed bloodshed in the armor of righteousness

Unbekannt. The Siege of Jerusalem, 1099. Miniature from Historia by William of Tyre, 1460s, Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon

III. The Sword of Faith at Home: Christian-Muslim Warfare in Spain

Religious warfare was not confined to expeditions abroad.

The Reconquista in the Iberian Peninsula (c. 711–1492) offers another rich field where faith and force intertwined.

The Christian kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, and León framed their long struggle against Muslim-ruled Al-Andalus as a holy war — a reconquest of Christian lands unjustly seized.

Royal chronicles, such as the Chronica Adefonsi Imperatoris, depict kings like Alfonso VII and later Ferdinand III as quasi-messianic figures, reclaiming Spain for Christendom.

Religious rituals saturated these campaigns:

Victories were celebrated with masses and the construction of churches on conquered ground.

Priests accompanied armies into battle, offering absolution to soldiers.

Muslim captives were often given the choice of conversion or exile.

Yet, as modern historians like Richard Fletcher have shown, the line between religious zeal and political opportunism was often blurred. Christian kings fought as eagerly against each other as against Muslim rulers when it suited their ambitions.

Still, in public imagination and official chronicles, the Reconquista was framed not as a political conquest, but as a holy obligation — an arc of history bending toward divine restoration.

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin. Torquemada at the Court of Ferdinand and Isabella Urging the Expulsion of the Jews. c. 19th century, Museo del Prado (attribution debated), Madrid

IV. Rituals of Faith and the Warrior’s Mind

Religion shaped not only why medieval wars were fought but how warriors prepared themselves to fight.

Before battles, it was common for knights to undergo confessions, receive blessings, and hear masses.

In the 13th century, the Rule of the Templars — the governing code for the Knights Templar — mandated strict religious observance: prayer seven times daily, rigorous confession, constant readiness to die in a state of grace.

Their military service was framed explicitly as a spiritual mission, a monasticism of the sword.

Even for secular knights, the idea of dying "in the service of Christendom" gave war a sacramental aura.

The medieval notion of the "miles Christi" — the soldier of Christ — merged the ideals of chivalry with Christian devotion.

Religion offered warriors a framework for facing death not with fear, but with purpose.

It offered the hope that the sword could become an instrument of salvation, not merely survival.

The Road to Agincourt (Mathew Ryan Wood, 2021).

Though united in armor and purpose, the lead rider’s downward gaze evokes the private hesitation that often hides beneath collective war. The uniformity of soldiers behind him becomes almost abstract — a visual metaphor for the fragmentation of the individual mind inside the machinery of faith and force.

V. To Conclude: The Cost of Conflating Heaven and Earth

Religion gave medieval warfare its banners, its blessings, and its bloodiest excesses.

It turned battles into pilgrimages, conquests into crusades, kings into champions of faith.

It provided moral certainty in a world of shifting loyalties and brutal violence.

But the fusion of faith and force also unleashed some of the darkest chapters in European history: massacres justified by scripture, atrocities committed under the sign of the cross.

The deeper tragedy is not simply that religion justified war.

It is that war, once clothed in the language of faith, became nearly impossible to question.

When violence is framed as sacred, it is no longer judged by human laws. It becomes an extension of divine will — or what men believe divine will to be.

In medieval Europe, faith shaped warfare profoundly.

And warfare, in turn, shaped faith — hardening it, weaponizing it, and leaving marks that would last far beyond the Middle Ages.

Works Cited

Gesta Francorum et Aliorum Hierosolimitanorum. Translated by Rosalind Hill, Oxford University Press, 1962.

Fletcher, Richard. The Cross and the Crescent: Christianity and Islam from Muhammad to the Reformation. Penguin Books, 2005.

Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The First Crusaders, 1095–1131. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Tyerman, Christopher. God’s War: A New History of the Crusades. Harvard University Press, 2006.

Einhard. The Life of Charlemagne. Translated by Lewis Thorpe, Penguin Classics, 1969.

Rule of the Templars: The French Text of the Rule of the Order of the Knights Templar. Edited and translated by J.M. Upton-Ward, Boydell Press, 1992.

aaaaa

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.