Logic is Not Neutral: Why Reason Still Needs a Foundation

By: Shreyas Jain

Date: 4/3/23

There’s a dangerous assumption behind much of modern intellectual life — that logic is neutral. That reason floats above culture, morality, and metaphysical commitment. That it simply “works” on its own, like a tool you can pick up and use without concern for who forged it, or what world it belongs to.

But logic, like language, arises from somewhere. It presumes order, coherence, intelligibility. It presumes that the world is not arbitrary — that contradiction is not just confusing but wrong. The question is: why? Why should the human mind trust that the universe is ordered in a way it can actually grasp?

It is not enough to say, “Logic is self-evident.” Nothing is self-evident without first admitting what counts as evidence — and that is already a metaphysical commitment. The rules of inference, the law of non-contradiction, even the belief that the past resembles the future — these are not products of reason, but preconditions for it.

Aristotle writing in a medieval manuscript.

Though often remembered for formalizing logic, Aristotle insisted it could not function without first principles — truths grasped not by deduction, but by intuition. Even reason, for him, had to begin in faith.

I. The Fragility of Pure Reason

The Enlightenment elevated reason as the final arbiter of knowledge. Descartes, famously, began with doubt and tried to rebuild truth from a single axiom: Cogito, ergo sum. But even Descartes relied on something more than syllogism. His belief in a rational God guaranteed that the clear and distinct ideas he perceived were not the tricks of a malevolent demon. In other words, he assumed the metaphysical order of the world before he could trust his logic to explore it.

Take that away, and what are we left with?

David Hume, operating downstream from Descartes but refusing the theological scaffold, exposed the limits of reason with terrifying clarity. We cannot logically prove that the future will resemble the past. We cannot derive “ought” from “is.” Cause and effect? Just habits of perception. Hume does not destroy logic — he simply reveals that its trustworthiness depends on assumptions it cannot prove.

And so we return to the metaphysical.

Unknown Artist. Portrait of René Descartes. 17th century, public domain. Colorized version reproduced in Philosophy Now, Issue 114

I. The Christian Presupposition of Order

What Christianity — and particularly Orthodox Christianity — offers is not a competitor to logic, but its cradle.

“In the beginning was the Word (Logos), and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (John 1:1)

Logos here is not just "word" — it is logic, structure, order, meaning. And that Logos is not an impersonal principle. He is personal. Incarnate. The world is not just intelligible — it is intelligible because it was spoken. Creation is not random. It is rational because it was made through Reason Himself.

St. Athanasius writes in On the Incarnation that the Word by whom all things were made “entered into the world as into His own.” There is no alienation between God and the order of creation. Logic does not float above the world. It pulses through it, rooted in its origin.

This is not a speculative luxury — it is a condition for knowledge. Without belief in some metaphysical ground of rationality, logic becomes what Nietzsche saw it as: a mask for instinct, a cultural artifact pretending to be eternal.

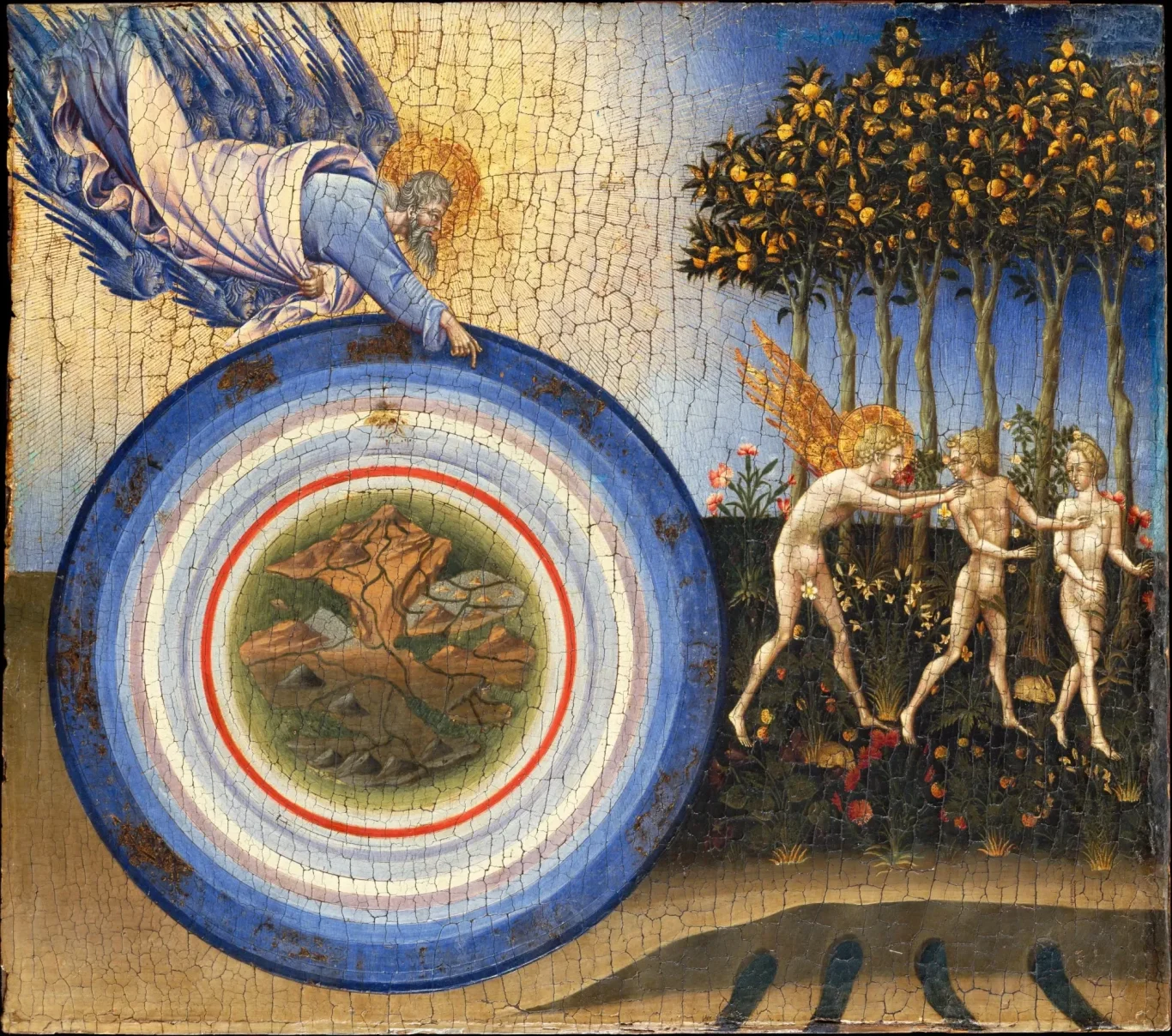

The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise (Giovanni di Paolo, c. 1445).

In this image, creation is not chaotic — it is ordered, layered, deliberate. Christian cosmology begins not in randomness, but in Logos — the Word that gives form, meaning, and direction to all things. This vision of order is what makes knowledge possible. Without it, logic would have no world to stand on.

II. The Myth of Neutrality

Even today, the most avowedly secular systems of logic are riddled with implicit metaphysics. The assumption that the universe is rationally structured. The assumption that human minds evolved to access that structure. The assumption that truth matters — that it is more than pragmatic survival.

The moral content is buried in the method.

You can see this even in the attempt to define logic as “that which preserves truth.” But truth, in this framing, is already taken for granted. Why should we think such a thing exists? And if it does — is it abstract? Eternal? Contingent? Embodied?

To invoke logic is always to invoke a vision of reality — even if that vision goes unspoken. And if the vision is incoherent, the logic built upon it begins to tremble.

III. Can Logic Function Without a Metaphysical Anchor?

Consider a world without God. A world where matter is all there is, where consciousness is an accident, and where evolution rewards not truth but survival. In such a world, logic becomes utilitarian. You believe what helps you live. Truth becomes adaptive fiction. If your reasoning happens to reflect reality, it’s an accident, not a certainty.

Alvin Plantinga presses this point sharply. If our cognitive faculties are the result of blind evolutionary processes aimed at fitness, not truth, then we have no reason to trust them — including the faculties that produce logic. In other words: naturalism defeats itself.

By contrast, the Christian claim is that our minds were made to know because they were made by the One who knows. The coherence between mind and world is not coincidence — it is communion. This doesn’t make logic infallible, but it does make its foundation trustworthy.

Courtroom by Susan Savad.

A courtroom holds authority only when it rests on something more than procedure. Like logic, law collapses into formality without a moral or metaphysical foundation to give it meaning. Empty chambers echo when justice is unmoored.

IV. Rationalisms Collapse into Power

Nietzsche understood this — and that’s why he sought to burn it down. He saw that once the metaphysical scaffolding of Christian thought was removed, “truth” became just another word for power. There were no facts — only interpretations. Logic itself became a tool for domination: who gets to define the rules? Who benefits when they are applied?

He was wrong in the remedy, but right in the diagnosis.

Once you declare reason to be self-contained — detached from metaphysical meaning — it becomes available for anyone to bend. What is “logical” can be made to justify cruelty, war, exploitation. The system may be internally consistent. But without a reference point beyond itself, it can only tell you how to argue — not why you should pursue truth in the first place.

V. Reason's Return to Wonder

None of this is an argument to abandon logic. It is an argument to ground it. To remember that reasoning is not an end in itself, but a response to a world already structured in meaning. We do not create order through thought. We discover it. And that discovery is only possible if something real — something stable and good — underlies the chaos.

In the Orthodox tradition, truth is not a proposition. It is a person.

Christ does not say, “I teach the truth.”

He says, “I am the truth.” (John 14:6)

This is not anti-rational. It is rationality’s completion. Logic is no longer a floating mechanism, but a bridge — between minds and between worlds.

To debate faithfully, to seek knowledge seriously, is not to detach from belief — it is to build from it. Without metaphysics, logic is air. With it, logic becomes the breath of a soul that was made to know.

Works Cited

Athanasius. On the Incarnation. Translated by John Behr, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2011.

Descartes, René. Meditations on First Philosophy. Translated by John Cottingham, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Giovanni di Paolo. The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise. c. 1445, tempera and gold on wood panel, The Met Cloisters, New York.

Hume, David. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. Edited by Tom L. Beauchamp, Oxford University Press, 2000.

John the Evangelist. The Gospel of John. The Holy Bible, Revised Standard Version, Thomas Nelson, 1952.

Plantinga, Alvin. Warrant and Proper Function. Oxford University Press, 1993.

Raphael. The School of Athens. 1509–1511, fresco, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City.

Savad, Susan. Courtroom. Digital artwork, Fine Art America, www.fineartamerica.com.

aaaaa

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.