The Problem of Evil and the Necessity of Law: A Philosophical Reflection

By: Shreyas Jain

Date: 5/3/24

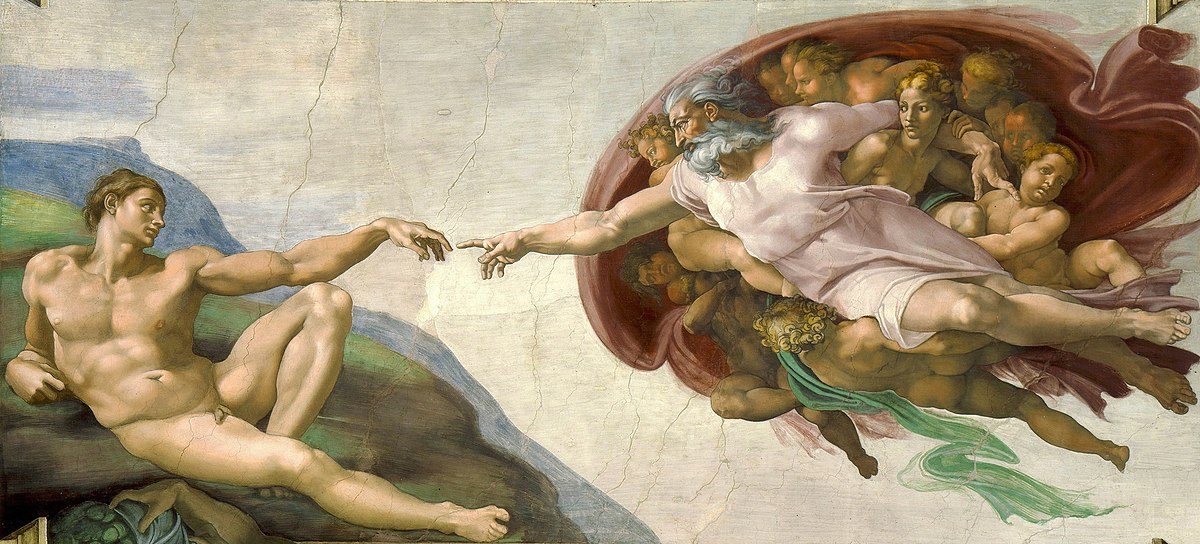

The Creation of Adam," Michelangelo, 1512. Sistine Chapel Ceiling, Vatican City

There is no world without evil. There never has been. Even the most careful designs of law, the most impassioned calls to virtue, collapse under the stubborn weight of human violence, cruelty, and betrayal. What law seeks to contain is not a mistake or an aberration. It is something far deeper: the ancient, wild energy at the heart of man, the will to transgress, to dominate, to destroy. The paradox is that law is not born from virtue, but from the recognition of vice. Law is the architecture raised in the ruins left by evil. And yet, if law merely suppresses evil without touching the soul, does it do anything more than cage what it fears? This reflection will explore that uneasy relationship: how evil necessitates law, and how law, in its efforts to suppress evil, sometimes comes to mirror it.

I. The Ancient Origins of Law and the Recognition of Evil

The earliest laws — Hammurabi's Code, the Laws of Ur-Nammu — arise not from philosophical speculation but from blood, vengeance, and fear. The law does not emerge because humanity first dreams of justice; it emerges because humanity first tastes chaos.

Augustine, in The City of God, argues that peace is the natural desire of all beings — but acknowledges that without the coercion of law, peace cannot be sustained. Human beings, scarred by original sin, turn even their better impulses into weapons unless restrained by external command.

For Augustine, law is not a celebration of human rationality; it is a grim necessity, an accommodation to a fallen nature. Justice — true justice — belongs only to the heavenly city. Earthly law can at best imitate its contours, always imperfectly.

In this view, law is an admission of failure: the failure of man to rule himself.

This is a more unsettling foundation for law than modern liberal theories often admit. Law is not aspirational. It is reactive.

It is the last fragile barrier between human nature and human extinction.

II. Evil as the Parent of Political Structure

Thomas Hobbes, writing amidst the English Civil War, strips away all illusions in Leviathan.

In the state of nature, he says, life is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." It is not virtue but fear of death that compels men to form political societies. It is not a dream of flourishing, but a nightmare of mutual destruction that gives birth to the state.

In Hobbes' cold, clear-eyed realism, law is the iron cage necessary to prevent men from devouring one another. Sovereign power must be absolute because the alternative — ungoverned freedom — is worse than tyranny.

Hobbes sees no innate goodness to build on. Law, for him, is not the expression of man's better angels. It is the chain binding the demons.

And yet — Hobbes leaves unanswered a troubling question:

If law arises from fear, what happens when law itself becomes the source of fear?

When the Leviathan turns predatory, where then shall man flee?

If the law becomes an agent of evil — codifying oppression, weaponizing fear — it reveals the fragility of any purely structural solution to evil.

Thus we glimpse a deeper tragedy:

Law is necessary because of evil — but law, being wielded by fallen men, can itself become an instrument of evil.

III. The Silent Ambiguity of Law

It is tempting to imagine that evil and law are simple opposites: chaos and order, darkness and light.

But this binary collapses under serious scrutiny.

Law, even at its best, does not eliminate evil.

It channels it.

It domesticates violence — transforming vengeance into punishment, conquest into jurisdiction, domination into governance.

Walter Benjamin, in his essay Critique of Violence, distinguishes between "law-making violence" and "law-preserving violence."

All law, he argues, originates in an act of force — a founding violence that then legitimizes itself by prohibiting future violence outside its own structures.

Thus, law and violence are not enemies. They are siblings.

Law is merely violence formalized and delayed.

This is not to say that law is illegitimate.

But it forces a recognition that law always carries within itself the seed of what it seeks to restrain.

In every courtroom, every parliament, every police badge, there echoes the first act of brute force that established "order."

The problem of evil, therefore, is not outside the law. It is folded into the law’s origin story.

IV. Dostoyevsky and the Internalization of Law

If the law cannot cleanse the world of evil, can it at least transform the heart?

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, in The Brothers Karamazov, poses the question brutally:

If there is no God, no ultimate accountability, what prevents man from doing anything he pleases?

Law, in Dostoyevsky’s world, is necessary, but tragically insufficient.

Without a deeper moral consciousness — without inner conversion — external law merely restrains behavior without redeeming the soul. It breeds compliance, not righteousness.

In the absence of true internal transformation, law becomes a brittle crust over a still-fermenting evil.

People obey not because they are good, but because they are watched.

Remove the surveillance, remove the threat of punishment, and the chaos returns.

Thus, Dostoyevsky offers a bleak insight:

Law without faith, without inner moral compass, is a scaffolding over an abyss.

This echoes in modern totalitarian regimes where law exists in abundance, but justice is nowhere to be found.

V. Law's Temptation Toward Evil

Because law is made by men, it is always vulnerable to the same darkness it seeks to restrain.

Hannah Arendt, observing the Eichmann trial, coined the phrase "the banality of evil" to describe how ordinary bureaucrats, through blind obedience to law and procedure, became agents of unspeakable atrocities.

The very structures designed to organize society can, under the wrong conditions, become mechanisms of mass murder.

When law loses its grounding in conscience — when procedure replaces moral judgment — the results are not chaos but highly efficient, highly lawful evil.

This is the final irony:

Law is created to combat evil, but without vigilance, it becomes the vehicle of evil in its most organized, most chilling form.

Law must therefore always be judged not only by its processes but by its purposes.

A legal system that is procedurally perfect but morally empty is not a triumph of civilization but a mask for barbarism.

VI. The Fragile Necessity of Law

Given all these dangers — that law is reactive, that it embeds violence, that it can be corrupted — why defend law at all?

The answer is simple:

Without law, evil flows unrestrained.

Law, however imperfect, creates space for mercy, for reasoned dissent, for appeals to higher principles.

It offers imperfect shelter against the raw storm of human malice.

But it must never be worshiped.

Law is not an end in itself.

It is a means: a provisional architecture erected in a fallen world, constantly vulnerable, constantly in need of renewal.

The necessity of law is not a celebration of man's wisdom. It is a confession of man's brokenness.

And it is a reminder that in every generation, the structures of order must be re-infused with conscience, or they will inevitably decay into instruments of the very evil they were built to restrain.

Works Cited

Augustine. The City of God. Translated by Henry Bettenson, Penguin Classics, 2003.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. Edited by Richard Tuck, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Benjamin, Walter. "Critique of Violence." Reflections, translated by Edmund Jephcott, Schocken Books, 1978.

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990.

Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Penguin Books, 2006.

aaaaa

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.