When Zarathustra Wept: Nietzsche, Pity, and the Limits of the Strong

By: Shreyas Jain

ox/ox/2x

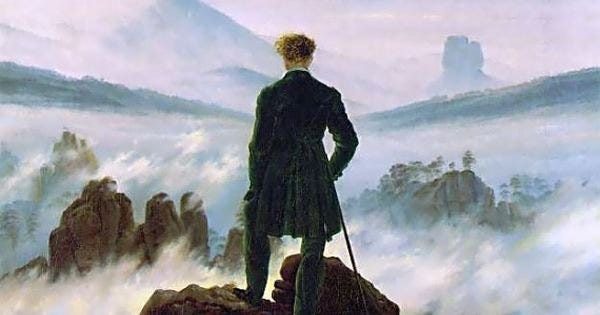

Friedrich, Caspar David. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, c. 1818. Oil on canvas. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany. Public domain.

I. The Shadow Behind the Übermensch

Nietzsche once wrote that Zarathustra descended alone from the mountain, not to comfort the weak but to awaken the strong. Yet buried in Thus Spoke Zarathustra is a contradiction: strength is celebrated, but something mournful haunts the text. It is the absence of pity, the deliberate rejection of it, that echoes most powerfully. In Zarathustra's encounter with the dying tightrope walker, pity is offered not as salvation, but as something to be conquered. "I do not like your pity," Nietzsche writes through Zarathustra, "keep your gifts to yourself."

What is left of man if he is denied the balm of sympathy? Nietzsche believed that pity enslaved, that it chained men to mediocrity. Yet, in his letters, he was a man in pain, fragile and lonely, confessing his vulnerabilities to friends who often abandoned him. This contradiction suggests Nietzsche wasn’t offering a doctrine from triumph but from the desire to become something he himself could never fully be. The Übermensch, the overman, becomes less a real figure and more a projection of unreachable strength—a strength defined by its refusal to kneel. But kneeling, we might argue, is sometimes the only human thing left to do.

There is power in resilience, but also in recognition. And the denial of pity may be the denial of relationship, of solidarity, of the very bonds that make any strength meaningful. Nietzsche's rejection of pity cuts deeper than theology; it questions the moral grammar of humanity. If pity is a weakness, then Christ on the cross—bleeding for others—is the ultimate fool. But if pity is a kind of strength, then perhaps Zarathustra never truly descended. Perhaps he remained forever on the mountain, preaching to no one but himself.

II. The Secret of Strength: Compassion or Will?

"The strong man is strongest when alone," Nietzsche asserts. But is he also the most hollow? In the Christian ethic, particularly in the writings of Dostoevsky, strength is often shown in the capacity to suffer with others. In The Brothers Karamazov, Ivan rejects God precisely because of the innocent suffering of children. Yet Father Zosima embraces that suffering, offering not rejection but redemptive solidarity. Nietzsche would scoff. But perhaps this scoffing conceals a terror: that the will to power cannot offer healing.

Dostoevsky and Nietzsche walk the same road but diverge at the heart. Both reject comfortable illusions, both despise hypocrisy, but where Nietzsche scorches the earth to clear it, Dostoevsky waters it with tears. Can we find in pity a kind of heroic endurance? Consider Prince Myshkin from The Idiot, whose kindness is so radical it borders on madness. Nietzsche would label him degenerate. But what if Myshkin is what the Übermensch fears he cannot become—someone who remains human despite knowing the abyss?

We mistake pity when we reduce it to patronizing sympathy. True pity requires proximity to pain, a willingness to suffer not above but beside. If the will to power builds mountains, pity descends into valleys. The strong may rise, but the compassionate endure.

III. Zarathustra’s Lament: A Missed Redemption?

Zarathustra never weeps. That is his tragedy. He preaches storms, dances with solitude, but cannot shed a tear for the broken. What would it mean if he did? If Zarathustra had knelt beside the tightrope walker and wept, would he have lost his power—or found his soul?

History is full of those who held both sword and sorrow. Marcus Aurelius, the stoic emperor, wrote in Meditations not about triumph, but about restraint, about inner mercy. Lincoln, leading a nation through civil war, spoke not of vengeance but of "malice toward none." Even Churchill, the icon of unyielding resolve, wrote speeches laden with human anguish. There is strength in control, but there is nobility in grief.

Nietzsche feared that pity softened the will. But perhaps it tempers it. In a world obsessed with domination, the capacity to mourn, to kneel, to carry another's burden, becomes revolutionary. If Zarathustra had wept, he might have been laughed at. But he might also have been remembered not just as a voice, but as a man.

IV. The Modern Übermensch and the Myth of Stoic Power

In the modern world, Nietzsche's ghost walks among us in curated self-reliance, stoic detachment, and the cult of personal power. Social media rewards invulnerability. Leadership punishes apology. To show need is to show weakness. We are all becoming mini-Zarathustras, descending from digital mountains to announce our self-made truths. And we are lonelier than ever.

Nietzsche warned against herd morality, but today we herd toward a new idol: the aesthetic of invincibility. The overman has become an influencer. Yet even he must log off at night. What if the real strength lies not in the posturing, but in the unseen moments—the friend who listens, the father who forgives, the stranger who cries?

The future must move toward a deeper strength, one that integrates will and wound. We do not need more overmen. We need men who can bear the world without crushing it. We need Zarathustra’s tears.

aaaaa

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.