Why Small Republics Fall: Lessons from Ancient Greece for Modern Democracy

By: Shreyas Jain

Date 2/12/25

I. The Fragility of Republics

The classical Greek world gave birth to numerous city-states (poleis) that flirted with republican forms of government. Most notably, Athens, with its radical democracy, and Thebes, with its mixed oligarchic-democratic structure.

Their size was both their strength and their weakness. Small populations enabled greater citizen participation, fostering a vibrant public life. But it also meant that the machinery of governance relied heavily on personal relationships, social cohesion, and a shared sense of duty — fragile things even under the best conditions.

When the delicate balance of civic virtue, institutional strength, and strategic leadership faltered, collapse followed with chilling speed.

In studying these republics, four recurring causes of downfall emerge:

- Internal Polarization:

Citizens divided into bitter factions, often prioritizing party or class over the polis itself.

- Demagogic Leadership:

Leaders who pandered to emotions rather than reason, prioritizing popularity over the long-term good.

- Institutional Decay:

Assemblies, councils, and courts lost their authority as corruption and partisanship seeped in.

- External Vulnerability:

Internal weakness invited conquest or manipulation by stronger powers (e.g., Macedon, Sparta).

The Death of Socrates (Jacques-Louis David, 1787)

II. Athens: A Cautionary Tale

Athens is often idealized as the cradle of democracy, but its later history reads more like a tragedy than a triumph.

Following the end of the Peloponnesian War, Athens entered a period of deep instability. Its democracy became increasingly dysfunctional — dominated by charismatic figures who promised easy solutions to complex problems.

Demagogues like Cleon rose by inflaming the fears and prejudices of the citizenry. Mob rule displaced reasoned debate. Important decisions, such as the disastrous Sicilian Expedition, were made impulsively and emotionally, leading to catastrophic losses.

Perhaps no moment better captures Athens' internal rot than the trial and execution of Socrates. A society once celebrated for intellectual freedom and debate found itself intolerant of dissent. Socrates was charged with "corrupting the youth" and impiety — but fundamentally, he was punished for questioning authority and challenging the comfortable illusions of the masses.

The execution of its greatest philosopher revealed a republic that no longer trusted its own foundations.

Athens did not fall because of overwhelming external enemies alone. It fell because it consumed itself from within.

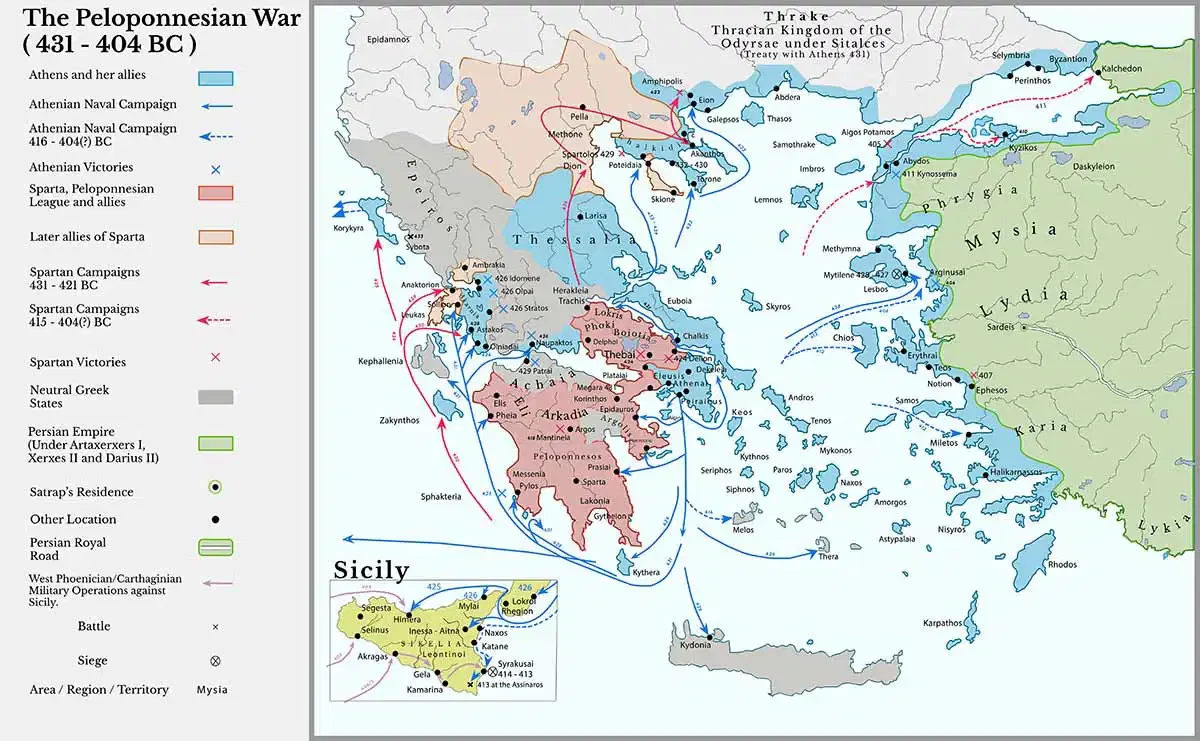

Map of Ancient Greece during the Peloponnesian War — a fragmented landscape of small republics, each striving for survival and dominance

III. Thebes: Rise, Glory, Collapse

Thebes offers another striking example, albeit on a smaller scale. Following the decline of Spartan hegemony after the Battle of Leuctra (371 BCE), Thebes enjoyed a brief moment as the preeminent power in Greece.

They implemented some notable political innovations, including broader enfranchisement and reforms aimed at reducing aristocratic dominance. But these successes masked underlying instability.

The Theban political elite struggled to balance internal rivalries. Leadership passed into the hands of men less skilled than their brilliant generals like Epaminondas. Without a unifying vision or strong civic identity, Thebes found itself vulnerable.

Philip II of Macedon, recognizing Thebes' weakness, moved swiftly to dominate Greece. The Theban political system, brittle and internally divided, offered little resistance.

Their fall was swift — not because their military was incompetent, but because their political soul had already frayed.

IV. Parallels to Modern Democracies

Looking across the centuries, the echoes are unsettling. Today, many democracies — both large and small — show signs eerily similar to the Greek poleis before their fall:

Rising Political Tribalism: Citizens increasingly identify with parties over shared civic identity. Winning becomes more important than preserving the system itself.

Demagogic Temptations: Charismatic leaders exploit public fears and resentments, often attacking institutions that resist them.

Institutional Weakness: Courts, legislatures, and watchdog agencies face increasing politicization and distrust.

Short-Termism: Strategic long-term planning gives way to policies designed to appease voters immediately, regardless of future consequences.

The mechanisms may be more complex — we live in vast, interconnected societies unimaginable to ancient Greece — but human nature has not changed as much as we might like to believe.

Republics, whether of a city-state or a continent-spanning superpower, live and die on the same principles:

trust, virtue, sacrifice, and reasoned governance.

Pericles and Boris Johnson: separated by 2,400 years, yet both symbols of leadership speaking to divided, uncertain democracies

V. Civic Virtue: The Missing Element

One consistent thread in every republic’s collapse is the erosion of civic virtue — the sense that participation in governance is a duty, not a transaction.

Civic virtue demands:

- Engagement over apathy

- Sacrifice over self-interest

- Respect for institutions even when they are imperfect

In Athens’ golden age, citizens served in juries, attended debates, and voted not because it benefited them directly, but because they understood the polis was bigger than any individual.

When that spirit decayed, so too did the republic.

Modern democracies must ask themselves: Is civic virtue still alive today?

Or has citizenship become something we outsource to politicians, engage with sporadically, and ultimately regard with cynicism?

If the answer leans toward the latter, the historical warning is clear.

VI. The Role of Leaders: Builders or Destroyers

Another critical factor is the quality of leadership.

When leaders:

- Respect institutions rather than undermine them,

- Encourage sacrifice rather than stoke grievance,

- Promote unity rather than division,

Republics thrive.

When leaders pursue only their own power, enabling factionalism, stoking resentments, and attacking constitutional norms, republics wither.

Ancient Greece offers abundant examples: Pericles’ early leadership stabilized Athens; his successors destroyed it.

Thebes thrived under Epaminondas; it crumbled under his lesser successors.

Leadership alone cannot save a decaying society — but bad leadership can accelerate its death.

Pericles spoke to a proud and hopeful Athens, celebrating the ideals of democracy. Yet beneath the triumph, the same divisions and complacency that would later destroy the republic were already at work — a warning modern democracies cannot ignore.

"A republic, if you can keep it."

Benjamin Franklin spoke those words at the founding of the American republic, echoing the silent lessons of Greece.

They remain as true now as they were then.

The question remains: Will we listen?

Works Cited

Hanson, Victor Davis. A War Like No Other: How the Peloponnesian War Reshaped the Ancient World. Random House, 2005.

Ober, Josiah. Democracy and Knowledge: Innovation and Learning in Classical Athens. Princeton University Press, 2008.

Plato. Apology. Translated by Benjamin Jowett, The Internet Classics Archive, classics.mit.edu/Plato/apology.html. Accessed 27 Apr. 2025.

Plato. The Republic. Translated by Benjamin Jowett, Dover Publications, 2000.

Polybius. The Histories. Translated by W. R. Paton, Harvard University Press, 1922.

Rahe, Paul A. The Grand Strategy of Classical Sparta: The Persian Challenge. Yale University Press, 2015.

Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Richard Crawley, Modern Library, 1951.

Franklin, Benjamin. "A Republic, If You Can Keep It." Notes from the Constitutional Convention, 1787. Recorded by James McHenry. The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, edited by Max Farrand, Yale University Press, 1911.

aaaaa

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.